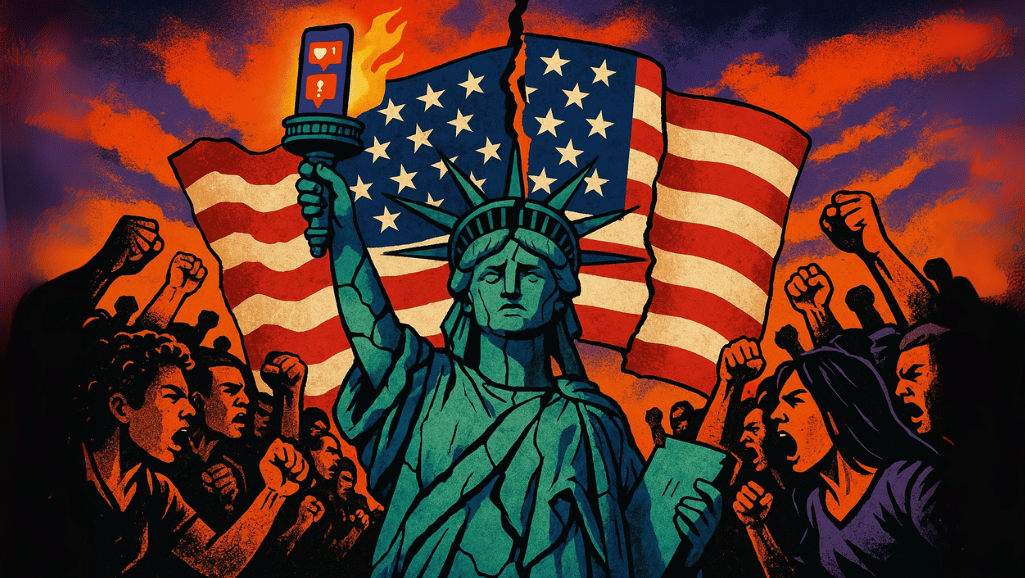

The Purge of They & Them: America's New Civil War

From Native massacres to slavery, immigrants to Muslims, America has always needed a “them.” Today, it’s tearing the nation apart.

In the days since the shocking assassination of conservative firebrand Charlie Kirk, America hasn’t mourned - it’s splintered. The nation has plunged into a cacophony of finger-pointing, facts tossed aside in favor of raw rage and hate.

The blame game began within hours of the murder, when President Trump went before cameras in the Oval Office to accuse the far left before investigators had even identified a motive or found the shooter. Hours later, he escalated: “We have radical left lunatics out there and we just have to beat the hell out of them.”

His allies rushed to back him. Steven Miller spoke of “uprooting” enemies inside the nation. Vice President J.D. Vance, appearing on what would have been Kirk’s own podcast, vowed to dismantle liberal institutions he called “terrorist networks.” In a disturbing and emotional speech, he declared that “there can be no unity” with a long list of people who don’t share his views.

Democrats were quick to point out that no leader on the left has openly celebrated Kirk’s death or said he deserved it - as some on the right did when Minnesota Speaker of the House Melissa Hortman was gunned down earlier this year. No prominent Democrat jeered at Kirk’s murder the way leading right-wing voices mocked the brutal attack on Paul Pelosi.

Journalist Mehdi Hasan offered facts to counteract the fiction, citing multiple studies that showed right-wing extremism was a long standing problem in America, and that “the single biggest day of political violence in our lifetimes was January 6th, 2021, when right-wing extremists attacked the Capitol.”

A 2024 Department of Justice report noted that “since 1990, far-right extremists have committed far more ideologically motivated homicides than far-left or radical Islamist extremists,” though according to The Daily Beast, the DOJ removed that report from its website after the shooting.

Though police have now arrested the alleged shooter - 22-year-old Tyler Robinson - it still remains unclear whether he was even wed to the ideologies of the right or the left. Commentators have already noted that Robinson doesn’t appear to fit neatly into either camp, but still, the shouting match has already made the story less about the murder and more about blaming the perceived enemy across the aisle.

So now America stands, as if perched on the brink of an all-new civil war, the blood still fresh, the truth still unclear, locked in a death loop of accusation, feeding on its favorite drug - the word “them.”

But none of this is new. This reflex - this addiction to blaming “them” - has been in America’s bloodstream from the beginning. It was the gift, and the curse, carried across the ocean and baked into the nation’s DNA centuries ago.

What we are living through now is only the latest flare of a wound first opened on American soil in the 17th Century.

This isn’t just this week’s news. It’s the echo of four hundred years, and a wound just as old. A wound first cut when ships first reached these shores, and one that now demands healing, or it will finish what it began.

The Rise of the Puritans

To understand America’s wound, you have to look back to the Puritans who founded the nation. Most of us know them as cartoon pilgrims in buckle hats and black cloaks, smiling at turkeys in the school pageant version of Thanksgiving, but the truth is much sharper than that.

The Puritans were no gentle pioneers. They were a hard-edged European movement born out of the Protestant Reformation that split Christianity in two in the 16th Century. And at their core was a single obsession: to separate themselves from the “others.”

For over a thousand years after the fall of Rome in the 5th century, Western Christianity was ruled from the Vatican, with the Pope at the center and Catholicism setting the rules. But in the 1500s, everything cracked when a German monk named Martin Luther nailed his protests to a church door, sparking a wildfire of rebellion that became the Reformation.

In England, amidst the upheaval, Henry VIII severed ties with Rome, denouncing its wealth and corruption, and declaring himself head of a new Church of England. On paper, it looked like a revolution, but in practice the new church still looked a lot like the old one. Henry only bailed because the Pope wouldn’t let him ditch his wife. Easy fix: make your own church, make your own rules.

The Puritans emerged in the wake of this split, children of the Reformation shaped by the radical theology of John Calvin, whose doctrine of predestination taught that God had already chosen who was saved and who was damned, and nothing anyone did could change it. Since no one could know for sure which way they were headed, life for them became a performance of purity: hard work, strict worship, plain living, and punishing dissent were all ways of signaling salvation. It wasn’t that these acts earned grace; it was that without them, you looked like one of the damned.

And damnation was so not cool in the 1500s.

But this obsession with purity put the Puritans on a collision course with the King’s new church, where they would soon be targeted as England’s “them.”

The First “Them”

To the Puritans, Henry’s Church of England still looked suspiciously Catholic. Cathedrals gleamed with stained glass, priests wore ornate robes, rituals reeked of incense and hierarchy. This wasn’t freedom. For Puritans, it was contamination.

So they demanded a stripped-down faith: no bishops lording over the people, no stained glass to distract the eye, no rituals that smelled of superstition. Just scripture, sermons, and the strict discipline of a godly life.

The Puritan way was to draw a hard line between “us” and “them” - God’s chosen on one side, the corrupt on the other. And the “them” wasn’t just Catholics in Rome - it was anyone clinging to bishops, rituals, or worldly indulgence, including their fellow Englishmen in the Church of England.

Puritanism became a veiled power play. Those who best displayed the signs of God’s favor claimed the right to enforce the rules. Fear turned into authority: if you could prove you were chosen, you could gain the power to decide who wasn’t. You proved your purity by proving someone else was impure.

All of this terrified the monarchy, who saw exactly what was at stake. “No bishop, no king,” King James famously declared. He knew if the Puritans toppled bishops, they wouldn’t just gut the church - they’d undermine the monarchy itself. So he set about othering them.

Puritan ministers were stripped of pulpits, fined, even jailed. Their gatherings were broken up, their books censored, their very identity mocked as fanatical. To the crown, they weren’t loyal subjects anymore; they were dangerous radicals. The more radical “Separatists” fared worst of all - hunted, spied on, their property seized, their lives made nearly impossible.

It’s the same reflex you see today: when a tyranical ruler feels threatened, they don’t argue - they other. The tactic is old, but the script hasn’t changed.

Some Puritans gave up and fled across the Channel to the Netherlands, while others sailed for America - not chasing freedom for all, but freedom for themselves.

They weren’t looking to build a land of tolerance; they were looking for a land where they could finally control the circle of belonging, and cast everyone else as “the other.”

Freedom for Us, Not for Them

In 1620, a small band of Puritans arrived in America aboard the Mayflower, landing at Plymouth on the edge of today’s Massachusetts.

Over the next decade, more Puritans followed with money, charters, and John Winthrop’s famous vision of a “city upon a hill,” pure and exemplary. But that vision wasn’t about shining as a beacon of diversity. It was about proving that a chosen people, fenced off from the world, could live righteously without interference.

And so America was established as the ultimate example of “us and them”. It was not a new land for all. It was a new land for “us” and not for “them.” The whole project was a reaction to the “other,” built not on inclusion but on exclusion.

From the first encounters with Indigenous people, cast as heathens and obstacles, the pattern was set: just as the Puritans had been othered in England, America would define itself by who it pushed outside the circle.

Erasing the First Americans

The Indigenous peoples of New England, who had lived on the continent for thousands of years, became the Puritans’ first true enemy in the New World - the Puritans new “them.”

In sermons they were branded “heathens,” “savages,” even the devil’s children - not simply neighbors but obstacles to God’s city. And once you cast people as agents of Satan, anything done to them can be justified.

At first there was uneasy trade, but suspicion soon hardened into violence. In 1637, Puritan forces surrounded a Pequot village at Mystic, Connecticut, set it ablaze, and cut down those who tried to flee. By dawn, seven hundred Pequots were dead. The Puritans called it a victory ordained by God.

A generation later, the blood returned. By the 1670s, the Wampanoag leader Metacom - “King Philip” to the English - had watched his people’s land carved away piece by piece. Broken treaties, trampled fields, and relentless encroachment left no choice but war. For two years, New England burned. Colonists woke to the crack of muskets and flames consuming their homes. Native villages were torched in retaliation. Entire towns vanished overnight. Thousands died; survivors were executed, enslaved, or driven west. Proportionally, it was one of the bloodiest wars in American history.

When the smoke cleared, the Puritans saw only proof of what they had always believed: the land was theirs, and “they” had no place in it. This wasn’t coexistence - it was extermination. Their freedom depended on erasure.

These wars weren’t only about land. They were about fear - of being outnumbered, swallowed by a continent already alive with other peoples, or abandoned by God. Fear turned massacre into righteousness.

From Mystic to King Philip’s War, America’s first experiments in freedom were written in fire and gunpowder, setting the pattern for a nation that would reach for violence whenever its power felt threatened.

No Room for Heretics

The Puritans didn’t just see the indigenous people as “other” - they responded with the same violent fury and “othering” when dissent rose inside their own colony. Quakers who refused to bow to Puritan authority were whipped through the streets, branded, or banished. Baptists who preached rival visions of baptism were fined and expelled.

When Anne Hutchinson - a midwife and mother of fifteen - began hosting meetings in her home, teaching scripture and offering her own interpretations of God’s word, people flocked to her gatherings, drawn by her charisma and her conviction that faith was about grace, not rigid works or obedience to church elders, but to the Puritan magistrates, this was intolerable. A woman claiming her own revelations from God and questioning their authority was nothing less than rebellion.

She was hauled before the General Court in 1637, grilled for days, and ultimately exiled from the colony. Heavily pregnant, Hutchinson was cast out into the wilderness and forced to seek refuge in Rhode Island. A few years later, she and most of her children were massacred in an Indigenous raid - a fate her Puritan enemies back in Massachusetts smugly interpreted as divine judgment.

Her story made the lesson plain that even inside the supposed “city upon a hill,” there was no room for a different voice. Conscience was policed. Revelation was punished. Dissent was met not with debate but with exile, the whip, or the noose. The brutality was, once again, all about fear - fear that one voice could unravel the whole order, that one woman’s courage could expose the fragility of their authority.

This was never a story of pluralism. It was a story of uniformity. The Puritans didn’t sail for freedom - they sailed to build a world without “them.” Violence was the tool they used to keep the ever-growing list of “thems” at bay.

And that wound has been bleeding ever since.

Chains That Built a Nation

No “them” shaped early America more deeply than the one forged in chains.

From the very beginning, the American colonies ran on labor, because someone had to work the fields. At first it was poor Europeans - indentured servants who signed away years of their lives to pay off passage - but servants were temporary, and they were still part of the “us.” They looked too much like the masters, shared their language and religion, and when their contracts ended, they became competitors. The ruling class needed a labor force that could never belong, never rise, never blur the line between master and servant - between us and them.

Africa supplied the answer. By the early 1600s, European ships were already prowling the West African coast, buying and stealing human beings to sell in the New World. In 1619, the first enslaved Africans were brought to the English colony of Virginia, and what began as a trickle became a flood. Ship after ship crossed the Atlantic, packed with bodies chained in darkness, a human cargo brutalized by the Middle Passage.

On American soil, Blackness was cast as permanent “otherness.” Laws hardened fast: Africans and their children were slaves for life. White indentured servants could work their way out; Africans never could. This wasn’t just economics - it was theology, politics, culture. Pseudo-Christian arguments painted Africans as cursed. Pseudo-science declared them less than human. Blackness was defined as the ultimate “them,” so that whiteness could define itself as “us.”

Slavery didn’t just build America’s wealth; it built its worldview. Plantations, auction blocks, and slave codes weren’t only about cotton or tobacco - they were about drawing an unbreakable line. Freedom, in America, was imagined by comparison: we are free because they are chained.

But slavery endured not just because it made money, but because it soothed fear. Ministers told planters the Bible itself ordained slavery. By making Blackness the eternal “them,” whites kept their terror of ruin and equality chained away.

Brother Against Brother

By the mid-1800s, the wound of slavery split the nation itself in two. The Puritans’ old reflex - freedom for “us” built on the exclusion of “them” - had hardened into two irreconcilable visions of America.

In the North, industrial cities and free labor built an identity around progress, commerce, and eventually the belief that slavery could not endure.

In the South, plantations and cotton fields built fortunes on enslaved labor, defended by theology, law, and violence.

Each side defined itself against the other. Both sides claimed God. The South’s preachers thundered that slavery was biblical order; the North’s invoked God’s judgment on the sin of bondage. Fear hid behind faith on both fronts - fear of losing power, fear of moral corruption, fear that God would damn the nation if the wrong side won.

The Civil War was the blood-soaked climax of America’s deepest “us vs. them” - not colony vs. Indigenous, not white vs. immigrant, but American vs. American. Brother killed brother, neighbor burned neighbor’s farm. By the time the guns fell silent, more than 600,000 were dead, and the wound had only shifted shape.

Even after emancipation, the “them-ing” never stopped. Reconstruction flickered and died. Jim Crow rose in its place. Lynching became a public spectacle, postcards sent home with the bodies of Black men hanging from trees. The Black “them” was recast as dangerous, criminal, a perpetual threat to white safety. In courthouse laws and back-alley violence alike, white America continued to define itself as “free” precisely by casting Black America as the opposite.

And the bitterness between North and South calcified into cultural memory, a division that lingers in politics and identity to this day. The Civil War didn’t heal the “us vs them” wound; it simply carved it deeper.

The Hungry Ships

Over time, the American fortress the Puritans built began to look like a beacon from the outside. To the starving, the persecuted, the poor, America glowed with possibility. The myth of the “city upon a hill” spread far beyond New England, until the whole world wanted in.

And so hungry ships kept crossing the Atlantic, with crowded decks full of people carrying little more than hope. Each wave arrived desperate for survival, each ship carrying a new “them” that was greeted with Puritan fear and hostility, that had now become bedded into the American psyche.

The Irish came in the 1840s, fleeing famine so severe it turned green fields into graveyards, and were met with “No Irish Need Apply” signs and ridicule. Italians followed, smeared as anarchists and criminals. Jews arrived seeking safety from pogroms, only to face whispers of conspiracy. And Chinese workers who built the nation’s railroads were repaid with riots and exclusion laws.

Every wave believed America meant survival. Every wave was met with the same suspicion: you are not us, you are them.

Only after decades did yesterday’s “them” get absorbed into today’s “us.” The Irish became white, Italians became neighbors, Jews became Americans. But by then, new “thems” were already stepping off the ships and into the streets - radicals with new politics, women with new demands, Black families seeking new lives, queer communities daring to exist.

The cycle never ended. The names just changed.

Witches in Modern Dress

In the 20th century, “them” wore new masks: communists branded traitors, feminists painted as enemies of the home, queer people hunted as corruptors. The details shifted, but the script stayed the same: they are dangerous, they are corrupting our children, they must be stopped.

This wasn’t just politics, it was panic. Fear found new costumes, but the sermon went unchanged: we are righteous only if they are cast out.

It didn’t matter whether “they” were suspected communists, outspoken women, or queer neighbors. America’s “us” once again defined itself by hunting the “them.”

Fear After the Fall

By the late 20th century, it seemed as if America’s walls were finally cracking. The “thems” were no longer silent. Black Americans marched and won civil rights. Women demanded and won the right to vote, then fought for workplaces and bodily autonomy. Queer communities rose from Stonewall and refused to go back into hiding. Immigration laws were loosened, and new cultures flourished in American cities.

For fifty years, from the 1960s onward, America seemed to be moving - haltingly, painfully, but undeniably - toward tolerance. Yesterday’s “thems” were slowly being written into the story of “us.” It looked, for a moment, as though the cycle might be breaking.

And then came September 11.

The towers fell, and so did America’s sense of safety. Muslims, Arabs, South Asians, even Sikhs in turbans became the new “them.” Mosques vandalized, neighbors surveilled, brown skin treated as a crime - the wound reopened overnight.

It didn’t matter that most were innocent. Truth wasn’t the point - fear was. And fear always resurrects the oldest American script: you can only be safe if the “other” is eradicated.

The scapegoat was chosen, the wound reopened, and the cycle rolled on.

The “Other” in the White House

In 2008, America did something unthinkable in the long sweep of its history: it elected a Black man president. Barack Obama’s victory was celebrated around the world as the triumph of tolerance, the final proof that yesterday’s “them” could become today’s “us.”

But beneath the cheers, a different current surged. For many white Americans, the sight of a Black family in the White House wasn’t just new - it was threatening. Obama’s rise triggered primal fear. His election cracked open the deepest fault line in the American story. The “them” had not only entered the circle; they had taken the highest seat inside it.

And then came the policies that pressed directly on the old Puritan nerve. Obama pushed for universal health care - “Obamacare” - a vision of inclusion that declared even the poorest had a right to treatment. To those raised on suspicion of the “other,” it felt like an invasion: their tax dollars flowing to those people. Under his watch, gay marriage was legalized nationwide, affirming the dignity of LGBTQ Americans. For conservatives who clung to the old fortress of family and faith, this was nothing short of desecration.

To many, his presidency looked like God’s fortress collapsing: it was preached as moral apocalypse, proof that America had fallen.

Every step Obama took toward inclusion - health care for all, equality for gay couples, a government that looked a little more like the people - was experienced by the old guard as proof of collapse. To them, the “city on a hill” was no longer shining. It was being overrun by “them.”

The backlash was swift. Conspiracy theories bloomed: Obama was a secret Muslim, born in Kenya, illegitimate. Right-wing media hammered the panic, painting him as an enemy within. The old reflex of fear reawakened.

The same wound, centuries old, was bleeding again: we can only be safe if the “other” is kept out.

The Enemy Within

It’s no accident that after Obama came Trump. America doesn’t swing gently between opposites; it snaps back like a wound reopening. Obama’s presidency placed the “other” at the very center of American life, and the backlash was inevitable.

Donald Trump saw the crack and drove a wedge straight into it. He rose by pushing the “other” button at full volume - immigrants, Muslims, Mexicans, refugees, Black protesters, queer and trans people, journalists, Democrats.

Trump told his followers the danger wasn’t out there somewhere. It was next door, across the street, sitting in the cubicle beside them. It was the enemy within.

That was the oldest wound speaking again - the Puritan reflex of purity and fear. Trump didn’t invent it; he stoked it, branded it, and rode it all the way to the White House. His rallies became revivals of grievance, a call to make America “great” again, which really meant make America “us” again.

And just like in Puritan New England, the logic was absolute. There is only “us” and “them.” To question the leader is betrayal. To defend “them” is heresy. To belong to “us” is to be righteous; to be cast as “them” is to be dangerous.

Trump’s rise wasn’t a new story. It was America’s oldest story, playing on repeat. But now the volume is louder, the stakes sharper. The country finds itself in a new kind of civil war - not North vs. South this time, but Republican vs. Democrat, left vs. right, state vs. state, neighbor vs. neighbor, family vs. family.

The slow erosion of togetherness has been building for years. Trust in institutions has collapsed. Shared truths have evaporated. The internet has turned every pocket of anger into a rallying crowd. Politics has become religion, and religion has become politics. Fear has metastasized into conspiracy, grievance into identity.

Half the country looks at progress - inclusion, equality, tolerance - and sees a promise finally being kept. The other half look at the same changes and sees an apocalypse. To one side, diversity is the flowering of the American dream. To the other, it’s the proof that the dream has died.

This is where centuries of “us vs them” have led: a nation tearing itself apart from the inside, each side convinced that if “they” win, “we” will cease to exist.

The Puritan wound, opened four hundred years ago, still bleeds in the headlines of today.

Pluto’s Return: The Shadow Rises

In 2022, America hit what astrologers call its Pluto Return - the moment when Pluto, the planet of the underworld, circles all the way back to the exact spot it occupied in the sky when the nation was born on July 4, 1776. It takes Pluto nearly 250 years to make that trip. No individual ever lives through one; only nations and empires do. And when it arrives, it brings one demand: face your shadow.

Pluto rules what’s buried - the rot beneath the floorboards, the corruption no one wants to name, the cycles of death and rebirth that can’t be dodged. A Pluto Return is the cosmic audit. Every empire that reaches it has to reckon with its deepest wound. Some transform. Most collapse.

Rome reached its Pluto Return and fractured. Spain reached its and lost its empire. Britain reached its in the fires of World War I. Every time, Pluto pulled the shadow to the surface, and the empire was forced to confront what it had built on.

Now it’s America’s turn to face its original wound; it’s addiction to “them.” The endless hunt for an enemy. The reflex to define freedom not by who belongs, but by who gets cast out.

For centuries the country has whispered, “this isn’t who we are” whenever the shadow has shown itself, but Pluto doesn’t allow denial. It rips the mask away and forces the wound into daylight.

Yes, America, this is exactly who we are, like it or not, and who we have been choosing to be since the very beginning. The shadow is now on the table. The wound is bleeding in daylight.

The only question left is whether we’ll face it and heal, or keep running until it kills us.

America’s Reckoning

Pluto doesn’t only expose - it demands a choice. America can keep replaying the cycle until it collapses under its own hatred, or it can do the unthinkable: break it. Imagine, for the first time, a nation that doesn’t need a “them” in order to be a “we.”

Because the brutal truth is this that the war on “them” has always been a war on ourselves. Unless that war ends, so does the American story.

This isn’t a deviation from the country’s path - it is the path itself. Every time America edges toward peace, the wound reopens. Violence isn’t just in the nation’s history; it’s in its bloodstream. The question now is what to do with it.

The choice is brutal but simple: heal or collapse. Strip away the mythology, own the blood in the nation’s history, and cut new patterns into the fabric. Or keep pretending, keep silencing, keep shooting, and let the republic die the same violent death it was born in.

The wound is rising because it’s ready to be cleaned, not hidden. The mirror is brutal, but it shows the truth: America’s sickness has always been “us vs. them.” Healing begins when the circle finally widens - when “them” is no longer cast out, when difference is not a threat but the proof of our shared survival.

The End of “Them”, The Turning of the Tide

At the root, there was only ever one reason the Puritans pointed their finger at a “them”: fear.

It was fear that set them against the Church of England, and fear that sent them across the sea in search of a land without it. When they arrived, it was fear that drove them to exterminate Indigenous people and silence dissent in their own ranks.

Fear enslaved Africans and resisted their freedom. Fear split the nation in civil war and slammed the door on immigrants. Fear saw communists under every bed, fought women’s suffrage and gay rights tooth and nail.

It was fear that sent soldiers to Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan after the towers fell. Fear that made millions suspicious of their first Black president, and fear that elected a conman to replace him.

And it was fear that pulled the trigger in Utah last week, and that same fear has stoked every accusatory tweet, meme, and headline since.

The same fear forged four hundred years ago on another continent is still alive in America today, tearing the country apart. This can go on no longer. We have to choose a better way. We have to tend to the nation’s oldest wound, and pouring more fear onto it is not the balm it needs.

The only elixir is love.

America’s Chronic Heart Problem

Love isn’t abstract. It’s how we act when fear tempts us. It’s refusing to retweet rage bait, asking one more question before assuming the worst, protecting the dignity of people we disagree with. Love is holding the line of humanity when everything in us wants to dehumanize back.

No president can legislate this. It begins with us - one heart at a time. Healing starts when we stop closing our hearts, even to those we disagree with, and even to those who hate us.

Love doesn’t mean rolling over; it means standing for what is right without turning opponents into monsters. It means advocating for justice and fairness in a way that widens the circle instead of shrinking it.

Fear only feeds the wound, and fear is never soothed by more fear. Only love can do that.

So start small: refuse the sneer online, listen a little longer, protect the vulnerable. Tiny refusals of fear add up. That’s how love moves from idea to culture.

When you look across the aisle and think you see only darkness, don’t shout it down, don’t tweet it into submission. That’s not resistance - that’s fear wearing the mask of strength. The harder, holier act is to lean out of fear and into love. To remember their light on their behalf, even if they’ve abandoned it. To hold it for them until the space between you disappears, and you remember that they are not your opposite - they are you. And you are them. We, the people.

Make this your mantra:

Even if you don’t honor me, I will honor you.

Even if you don’t respect me, I will respect you.

Even if you don’t love me, I will love you.

Because you cannot take that from me.

My light will not dim because yours has faltered.

I will hold the light for both of us.

If enough of us refuse the “them,” America heals - not in Washington, but in us. Fear divides, but love remembers.

I am you, and you are me. There is no “them.” Only us.

One nation, indivisible. This time, for real.

My intention in my writing is to lessen the climate of fear around world events by offering clarity and cosmic context for what’s unfolding; to bring context to the chaos. I believe our highest calling right now is to anchor in the vibration of love & truth and call in a more beautiful world, and to do that, we must lean out of fear. I hope you read this with an open, uplifted heart.

What an incredible post this is. All that history certainly helps make sense of what we’re witnessing now. I was utterly absorbed as I read this piece, seeing the interconnection and parallels across the centuries. Thank you as always for such an inspiring and informative read.

Thank you, Wizard - great article!

By the way, John Calvin was such a weasel - he hated/feared the body, hated/feared women and hated/feared Nature. And believed his own wealth was ordained by God. What a horrible legacy we have dragged forward from the Puritans and Calvin! All that hatred and fear that must be faced. Thank you for holding up a story and path of reconciliation and healing.